The 1982 Pacific to Atlantic Transcontinental Reliability Tour, Pebble Beach, California to Jekyll Island, Georgia

/Written by Howard Henry. Photos by Jim Conant, Millard Newman, John Silberman & Howard Henry. Originally published in The Bulb Horn, 1982, Volume XLIII No 4.

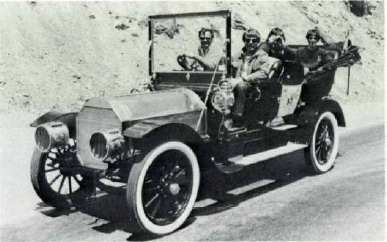

Scott isquick somewhere in the rockies

Fifty-one courageous owners of 1914 and older cars plus three loyal tour marshals showed up at Pebble Beach, California on June 22, 1982 to participate in the fifth VMCCA transcontinental trek across the United States. Months of planning and preparation were on the line, and with the cars shipped, driven, or trailed to the starting point, there was no turning back. The list of participating cars read like an automobile Who’s Who. There were twenty-eight different marques. Rolls-Royce was predominant with four beautiful Silver Ghosts. There were three each of Cadillac, Chalmers, Ford, Packard, Pierce-Arrow and Overland. Among the rarer cars were an Abbott-Detroit, a Cole, a Knox, a Moline and a Pullman. Over eighty percent of the entrants were old-timers, five having completed all five tours, and ten cars were piloted by rookies. Seeing all the beautiful, shiny cars and meeting up with so many talented and knowledgeable friends made Pebble Beach seem the only logical place in the world to be on this particular day.

The Technical and Safety Committee, under the direction of Chairman Ernie Gill and his nine assistants, ran the cars through a safety check. Each car was inspected for brakes, lights, steering, horn, safety glass and fire extinguisher before it was given a tour sticker for the windshield. Very few adjustments had to be made for the cars to pass. In our triptik Tour Director Millard Newman stressed that safety on the tour was of prime importance: “This tour is not a race, but a reliability tour, and therefore the winners will be determined by a system of check-points.” Veteran checkpoint tabulator Dorothy Conant handled her thankless job efficiently. She must still be asking in her sleep. “Were you towed, pushed or trailered more than 50 yards?”

The kick-off banquet was held at The Lodge at Pebble Beach where Millard Newman again stressed safety, courtesy and appreciation to VMCCA for sponsoring the tour and to the Quaker State Oil Company for supplying all the cars with free oil and grease at checkpoints in San Francisco, Lamar, Colorado and New Orleans. VMCCA President Dick Flemings headed the Financial Committee, and Susan Young registered everyone and handed out the tour packs, banners, schedules, etc. Marian Joset handled the trophies, and Judy Henry wrote, typed, printed and distributed The Tattler, the tour newspaper, and as advertised, it came out “semi-occasionally”. The tour route had been studied and selected by Director Millard Newman.

All the entrants got together in the parking lot at The Lodge and left the grounds at 9:00am on June 23rd, heading for the first checkpoint. Almost all of us left. Unfortunately, veteran tourist Tom Lester, driving a 1909 Lozier, had suffered a back injury while playing golf on the famous Pebble Beach course. His injury worsened, and although Tom had his car driven onto Reno, he was forced to undergo surgery in a San Francisco hospital and withdraw his car from the trip. Joel Naïve found a cracked block in his 1911 Pope-Hartford in time to get an extra engine shipped up from his home in La Jolla in Southern California. As we were leaving Pebble Beach the new engine was being installed in he Pope, but it, too, had problems. Somehow Joel got it all together several days later, rejoined us in Reno and finished the entire trip in grand style. Route 1 northwards to San Francisco had beautiful vistas of the rugged Pacific shoreline and some precipitous hills along the way. We came across Larry Kraus at the bottom of the steepest hill we had seen that day. He had lost both foot and emergency brakes, sped down the hill through a stop sign and came to rest beyond the intersection. The Tattler reported, and I quote with special permission, “The Pullman finally came to rest and the good guy in the white hat, Jerry Durham, diagnosed the problem as a detached torque bar, an important rod that holds the back to the front.” Larry was to continue to have numerous problems with his newly restored car, but he stayed with thm and made it all the way to Jekyll Island.

June 24th was a rest day. It gave us all a chance to grease our cars, check where all those funny little noises where coming from and to put things in better running order. One scene I will never forget was described in The Tattler thusly: “The Lodge at Pebble Beach was the epitome of elegance, but almost outdone by a scene in the garage at the Hilton in San Francisco. The table with white cloth, crystal, silver and fine wine set up beside Henry Petronis’ Winton, with tired, greasy enthusiasts eating steak, rivaled the dining facilities at our starting point.” They got the Winton fixed in style. Some of us were fortunate enough to spend some time with Alice Huyler Ramsey, the first women to drive a car across the United States. She has described the trip in her book, Veil, Duster and Tire Iron. She performed the feat in 1909 in a Maxwell, just one year after the 1908 Great Race around the world.

On Friday, June 25th, we worked our way out of city traffic, crossed the Bay Bridge to Oakland and motored through orchards, walnut groves and productive farming country which quickly changed into barren, deserted mining country and the beginnings of mountains. Sonora, California was our destination, and it turned out to be a picturesque western town located on one long street running up the valley. The buildings were old, and many had false fronts. One could picture the days of gold and silver mining that had taken place there. Ernie Gill worked long and hard on Ben Caskey’s Olds Autocrat, installing a temporary fan to replace the one that had broken. The Tattler editor had some problems, too. She was able to borrow the motel’s typewriter, but the only duplicating machine in town was across the street in the library. It was strictly a dime-at-a-time device, and when she ran out of coins she walked back and canvassed the parking lot, finally garnering enough to get the paper out in time.

The 26th was a fine day for motoring. We left Sonora, heading for Chinese Camp and Tioga Pass. At this point (about 2,000 feet elevation) one had slight comprehension of what climbing was ahead. The roads approaching Yosemite Park were excellent, lightly traveled, and the long climb from Hardin Flat up to Tuolumne Meadows was a gradual but steady ascent. For 35 miles we climbed; the park, the snowy mountains, the lakes and a whole changing scene developing before us. The wind got stronger, the air colder and so did the passengers. The summit of Tioga Pass is 9,945 feet high, the crest of the Sierra Nevada range. We paused at Tioga Pass Resort for gasoline and then took off on the spectacular and steep nine mile descent to Lee Vining. It was a tremendous downgrade, and huge snowy mountains were all around us. Our second gear kept our speed pretty well under control. It was a relief to finally reach the bottom of the mountain. We turned north on U.S. Route 395, our first intersection in 60 miles. We headed five mile north where a group of us stayed over night at the first “On your own” stop. Our route took us past the eerie appearing and slowly receding Mono Lake. There was one more climb that took us over Conway Summit (elev. 8,138 feet), and then we happily settled down at our motel in Bridgeport, California.

Tour Director Millard newman’s 1911 Rolls-royce

On the 27thwe continued our northward curse toward Reno, climbing Devil’s Gate Summit, our last pass in California. About 11:00am we saw the Nevada welcome sign. We passed through Carson City, the smallest state capital in the U.S., Judy and I taking a side trip to Virginia City via Empire, Silver City and Gold Hill. We had gone to Virginia city on the 1968 Tour, but I had forgotten how barren and high it is. A native told me that a big red Rolls-Royce with Florida tags had passed through ahead of us, so we assumed our Tour Director also revisited fabulous Virginia City. Some of the tourists took a western swing to Lake Tahoe, then on to Squaw Valley for the annual Swap Meet.

John silberman’s 1913 peugeot

The 28th of June was a rest day with a tour of the Harrah Museum as the main feature of the day. About forty of the museum’s most outstanding cars will be making an eleven city tour starting in September, so the collection is alive and well. The complex in Reno is still the greatest in the world. Arrangements had been made for our group to visit Harrahs for only half price. What a great collection! Several of us made a trip to a recommended radiator shop to see if we could improve our water circulation and reduce overheating. Both Dr. Bud Stanley’s big 1914 Cole and our 1913 Packard were running high fevers. The treatment seemed to make both cars run better. In the afternoon we motored out to the suburbs for a cocktail and hors d’oeurves party hosted by Tom Batchelors. It was lots of fun and gave us an opportunity to meet many of the Reno car collectors.

We left Reno on the 29th, heading east, and found ourselves nearly drowning in the cold, wet rain. The Reno Bank thermometer flashed 46 degrees. As one person put it, “The wet-chill factor exceeded the wind-chill factor by twelve.” Our destination was Fallon where the Northern Nevada Region of the AACA was to host our group for a coffee and dessert stop at Churchill County Museum. The museum in Fallon deserves special mention. Not only were the volunteers in the building well-versed in their subjects, but they went out of their way to explain their rarities. The museum had a wide range of early Americana, from a framed display of half-moon shaped ox shoes to gorgeous China from the Orient. There was even a large corkscrew collection! The music boxes, player pianos, old clothing, tools and farm implements were outstanding. One could only ponder at the sacrifice the early pioneers made in bringing their treasured possessions with them. Fine pianos, carved furniture and imported sets of china must have been hard to transport. The Paiute and Shoshone Indian artifacts display was unique. It featured a reed Indian hut, complete with wooden and stone utensils with detailed pictures and diagrams. The collection of tule and reed baskets, hats and duck decoys was interesting. Reed decoys are known to have been made almost 1000 years ago.

We arose early on June 30th for a run across some pretty barren country. It was cool and fine motoring, but we stopped at Frenchman, Nevada to gear up for the black louds and certain rain that loomed ahead. The storm lived up to its looks, the temperature dropping to 50 degrees and the rains coming in torrents. It soon passed behind us, and we crossed the flats to Austin, Nevada, a quaint western town. If the automobiles were removed, it would look as it did in the 1880s. We ate in the International Hotel, moved piece by piece from Virginia City in 1863, boardwalk and all. Austin had been a flourishing mining center featuring saloons whose massive, mirrored bars had been shipped by sailing raft around Cape Horn. Its railroad was built around 1880 from Battle Mountain to run up the main street of town. It hauled the loads of ore that produced $50,000,000 in silver until operations ceased in 1936. Stokes Castle, built in 1897 by financier Anson Phelps Stokes, is an exact copy of a granite tower on the outskirts of Rome. Silver was discovered near Austin when a Pony Express horse kicked over a rock that showed a rich vein of silver ore. Although the Pony Express was short-lived (April 1860 to October 1861), its name has outlasted any of the old railroads. Austin was truly a page out of the past.

On July 1st we climbed out of Austin to Austin Summit (elev. 7,484 feet), again in the cold rain, temperature 44 degrees. It was reported that this was the most rain they had had since 1913. Some of us stopped in Eureka for lunch, and it, too, was another page out of the history book of the Old West. Of interest to motorists was the original Lincoln Highway monument and a bronze plaque saying that General Motors had financed that particular section of the first transcontinental highway. We arrived at Ely where we were welcomed by the White Pines Historical Car Club, a most generous group. Our economy hotel was unable to provide a typewriter, so the chairman’s wife, Mrs. Hazel Baber, motored to town in her Essex Super-Six coupe and handed the Tattler editor her own machine. We found out that the club was providing helicopter assistance for any breakdowns of old cars along the highway. Ely was an old mining town and the site of the world’s largest “Glory Hole.”

Main street, eureka, nevada (right to left) Marshall’s steamer, henry’s packard, grundy’s packard

a water hose delivers vital liquid to tom marshall’s 1912 Stanley

1912 oldsmobile of ben caskey, jr, boca raton, florida

On July 2nd we got off at 8:15am. It was the first really clear day, and it seemed as if we could see forever. The terrain had become dry and barren, and somehow our car was labouring even though the road seemed to be going downhill. We tried to coast and the car slowed up. This was perplexing, especially since the stream beside us appeared to be flowing uphill. Naturally this could not occur, but many of us experienced this optical illusion reminiscent of Magnetic Hill in New Brunswick. We made a stop at a home where several of our cars boiled. It was pretty much in the middle of nowhere, and the owners were gracious enough to have rows of plastic jugs full of mountain spring water lined up on their front lawn. The water was free for the asking. These thoughtful people regularly provide water for overheated modern cars and were delighted by the visit of several pre-1915 cars in need of refreshment. They lived so far out in the country that every telephone call they make, even to their nearest neighbor, is automatically a long distance call. This was our day to enter Utah. We continued to drive through miles of hot, arid plains and rugged outcroppings. At one point the road across a valley was nineteen miles without a turn. As the road ran lower and the valley got hotter we passed by forty mile long Sevier Lake, a spectacular junior version of the Great Salt Lake. We went through Hinkley, a town where every stop sign had three or more bullet holes in it, even in the middle of town! We drove a few miles further along to Delta, Utah, not to be confused with Delta, Colorado. Delta was a friendly place and the Chamber of Commerce invited us to display our cars in the town square where each driver was presented with Cambrain Tribolite 550,000,000 years old! The tiny fossilized creature put things in perspective and made us and our cars seem suddenly very young.

Gill, henry and snyder with sevier lake (dry) in the background

On July 3rd we gassed up and checked our radiator in Salina, Utah. Our AAA triptik described our road as “a high desert route, crossing farm and cattle rangelands; offering good views of rivers, canyons, mountains and plateaus. No gasoline or services between Green River and Salina.” Nearly 108 miles of desert! It was said to be a tough stretch in a modern car, but thankfully the antiques showed what they were made of and old gas and brassers came through. Brent Campbell and Tom Marshall, who made it in steam cars, deserve special mention. You could well understand why Utah was the first state to take up and develop irrigation. We were in jack rabbit country, and judging from the number of them squashed on the road, we wondered how any of them could be left. We actually counted 44 and 74 dead jack rabbits in two separate one mile samplings, which would average out to over 5,000 rabbits every 100 miles. It seems incredible that the desert could support that much life. The scenery became more rugged and rocky. There were huge buttes, spires, towers, deep gorges and canyons, all carved by natures hit and miss erosion. As we descended the last six mile six percent grade, the rocks became redder and finally we came into the flat valley where the green on each side of Green River looked a couple miles away but was actually a two hour drive. I continually asked myself, “How did the pioneers ever make it?”

The 4th of July was our day in Grand Junction. The Colorado West Chapter of the VMCCA had invited us to be in their parade, celebrating both the Fourth and the Centennial of Grand Junction. The parade was a great sight and people must have come from miles around to enjoy he spectacle. Back at the motel in the late afternoon we were entertained by music from a huge calliope. Two little girls, Candace Kraus and the Solon Sprinchorn’s grand-daughter, Carolyn Pratt, put on a marvelous show of their own as they danced spontaneously for more than an hour to the music in the parking lot. A barbershop quartet was also part of the program, an added pleasure.

a couple of antiques dwarfed by the utah mountains

July 5th was one of the most challenging days. We were within sight of the snow covered Rockies and climbed gradually but surely up the Uncompahgre River Valley for a hundred miles to our lunch stop in Ouray. The Mountain and Plains Region’s Colorado West, Montrose and Ouray Chapters of the VMCCA arranged our cookout luncheon in an attractive little park. It was nice to get such generous treatment, and the food was delicious. However, our minds were focused on that pile of rocks interlaced with dozens of switchbacks that was called Red Mountain. From our vantage point it might as well have been Mt. Everest! About 1:00pm we started up the “Million Dollar Highway,” so named because it cost that amount each mile to blast a roadway out of the canyon walls in the early 1900s. The road was very narrow and tortuous, and the shoulders were only a foot wide in places. There were few guardrails, and the drop-offs were precipitous. It was an exciting grind all the way up to the 11,018 foot summit. We passed a number of abandoned silver mines, motored on for several miles and dropped down a couple of thousand feet to find ourselves in the picturesque town of Silverton (elev. 9,318 feet). Silverton is the northern terminal of the Durango and Silverton Railroad, the last regularly scheduled narrow gauge railroad in the United States. The town had a fine museum, an outstandingly restored main street, and their mayor was thoughtful enough to present us with certificates inscribed “Vicimus Super Rubrum Mons.” We conquered the Red Mountain. We climbed out of Silverton, up and down two more passes, and finally made the descent to Durango, a small town only eighteen miles north of the New Mexico border.

the hechts in their 1913 fiat. “cowcatcher” aids cooling

Scott and june isquick wave to the photographer

The 6th of July was a rest day in Durango. Thanks to Charlie Bradshaw, a fellow car collector from Orlando, Florida, a specially scheduled train stopped right behind our motel, the Iron Horse Resort, and took the tourists up the Animas River Valley to Silverton, returning about 3:00pm. Our Tour Director planned a rare bit of entertainment at the Bar D Chuckwagon, a western style barbecue dinner with country music at its best. We were taken to the Bar D in a 50-passenger bus, a 16-ton job with 4 tons of people in it. We crossed a bridge plainly marked “Maximum weight limit 2 tons.” When questioned about the bridge’s safety, the driver told us his boss had called the road department that morning and they thought the bridge was safe. We held our breaths, and the bridge held up! The Tattler later reported “Pac-At tourists used in Durango county experiment.”

1913 stevens duryea belonging to william D. Evans, san diego

On July 7th we braced ourselves for the trip over the Continental Divide at Wolf Creek Pass (elev. 10,857 feet). The mountain had an excellent highway up, with plenty of room to pass. It was a long, 7% grade, and again the scenery was spectacular. We had left the Colorado River drainage basin which flows south into Mexico and the gulf of California. Dropping down off Wolf Creek Pass, the first town we saw was South Fork, so named because of its spot on the Rio Grande River which empties into the Gulf of Mexico. The next day we were to begin our seven day association with the huge Arkansas River. It was the beginning of our gradual 1,300 mile descent to New Orleans and the sea level once again. Many of us stopped for the night Alamosa where the usual fixing and general tinkering went on.

The 8th of July was clear, bright and cool. The countryside was beautiful with rolling cattle ranges. There seemed to have been more rainfall, the hills being greener and the cattle fatter. We pushed over La Veta Pass (elev. 9,413 feet), our last real climb and our final view of the snow-capped mountains. Our destination was Pueblo, Colorado where we were hosted to a cocktail party and generous hors d’oeuvres by the Pueblo-Arkansas Valley and the Pikes Peak Chapter of the VMCCA. At this meeting it was our pleasure to be introduced to Francis M. Stanley II from Santa Fe, New Mexico, grandson of the co-inventor of the Stanley Steamer. Mr. and Mrs. Stanley were guests of steam driver Tom Marshall.

On Friday, July 9th we left our friends in Pueblo and headed for Lamar, Colorado. About 65 miles southeast we came into the town of Rocky Ford. The village did not rate a “point of interest” star on the triptik but should have a world-famous star for being the home of the Rocky Ford cantaloupe. About twelve miles further on we were hosted at a coffee and cola stop a the friendly town of La Junta where each car was presented with a centennial pennant. Leaving La Junta, we passed through Hasty (slowly) and a series of cattle feedlots with thousands of cattle to be fattened for the Eastern markets. The skies were dark and ominous, and as we approached Lamar a wild cloud formation was threating. It only rained, however, and no tornados developed. That evening the cocktail party was giving by Dale and Nancy Westermeyer of Kennewick, Washington. It was their 31st wedding anniversary.

1912 winton owned by henry and edith petronis

On July 10th we departed from Lamar and within an hour crossed the state line into Kansas. We had left the huge cattle ranches in Colorado to find ourselves driving by large wheat fields and hay farms. The 150 miles passed quickly and we were in Dodge City early. Boot Hill was a featured attraction, and it gave us some insight into pioneer life. The shooting abilities of Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson became legendary as they tried to maintain peace between cowboys, Indians, Confederate soldiers, and rail-roaders. It was in 1872 that the Santa Fe Railroad finally reached Dodge City, just 110 years before our tour stopped there. The museum was excellent, and the collection of Santa Fe Railroad items deserves special mention.

rather than miss the tour when their 1914 marmon soured, james shaw served as a tour marshall in his stutz

July 11th found us heading due south, and within 50 miles we entered Oklahoma. The countryside was green with gently rolling rangelands and frequent oil pumps. The hills were treeless except around the homesteads. Judy and I headed on south for 20 miles to Slapout and photographed our car at the Texas State marker. We retracted our route, heading east on the prescribed road, and promptly ran out of gas near Freedom, Oklahoma. We were rescued by the first pickup that came along, and while we were pouring in some gas John and Andy Grundy came along, overjoyed to find us in such an embarrassing fix. I do not think that I am a vindictive person, but I must admit I was delighted to learn that John ran out of gas the next day. We didn’t have many secrets on this trip. On this same day Karl Summer, Jr. had a tie rod problem with his five-time Transcontinental Tour 1913 Overland, and our Packard developed a progressive manifold crack.

ed swearingen’s 1911 Rolls-royce

The 12th of July was a short run, about 80 miles, to the luxurious Williams Plaza Hotel in Tulsa. It had a “tops down” indoor storage garage where all the cars were together. Tom Marshall had had a serious leak in his boiler for several days, and his assistant in steam, Weldin Stumpf, brought a new boiler to Tulsa from Yorklyn, Delaware. In two days, they had the boiler installed and even put in a replacement engine that Brent Campbell had thoughtfully brought along. With the new internal parts, Tom and his navigator, Bob Reilly, made it all the way to Jekyll Island and then the additional 850 miles home to Delaware.

1907 pierce great arrow of john hovey, wyckoff, new jersey

Our evening and dinner was arranged by Jim Leake of Muskogee, Oklahoma at a gorgeous home made into an art museum. Mr. Leake had brought his own chiefs from his restaurant to the museum where we dined outdoors in royal splendor. He had us transported to the museum in aged and elegant English busses. One vehicle had a little magneto problem, which one of our experts corrected. After dinner we wheezed back in the ancient busses to downtown Tulsa, enlightened by the stimulating art museum. Our second evening in Tulsa combined two special birthdays of two special tourists. Somehow the numbers were the same. Andy Grundy’s cake indicated 16, but the numbers on Whitney Snyder’s cake were the reverse. Andy has come a long way since his sixth birthday on the 1972 tour – 14,207 transcontinental miles to be exact. Whitney has also come a long was since he bounced across the country in his 1909 Mercedes in ’72.

We left Tulsa on July 14th for the two-day drive to Little Rock, Arkansas. We had a delightful luncheon stop at Antiques Inc. in Muskogee, the museum complex owned by James Leake that houses one of the world’s largest private collections of Rolls-Royces and Bentleys. One of his most outstanding vehicles was a Foden steam lorry which he ran for us. A lasting memory that we could take home with us was Jim’s talk on Oklahoma history. He told us how the territory had developed from American Indian and early white explorer times, down through the days of conflict, occupation, and eventual settlement. Our route left Oklahoma at Muldrow, crossing the Arkansas River into downtown Fort Smith. Unfortunately, this was the day for W.A. and Ruth Kidder’s Overland roadster to shear its driveshaft pin. The Washington group, headed by veteran Jerry Durham, went to work and got the reliable car back on the road. I’m sure that Cork Simmelink, a pharmacist and an expert on unusual diseases, supplied all the needed splints, band-aids and alcohol (ethyl, that is.)

July 15th found us headed southeast down the Arkansas River valley, our surroundings changing rapidly. There were many more and much larger trees, lots of well-fed livestock on the farms and more substantial buildings. Some of the tourists left the route at Perry to visit the Pettit Jean Mountain Museum. Several groups of us found our way to the Cajun’s Wharf, a colorful restaurant located right on the Arkansas River where commercial barges propelled by tugboats were still able to operate, nearly 500 miles up from the Gulf of Mexico. The food was excellent, but the décor was even better. Upon entering, the first thing we saw was a real live, scantily clad girl swinging in a swing hung from the ceiling overhead!

ken walter’s 1909 emf parked in line with the rolls-royce of newman and isquick

cork simmelink getting “directions” in new orleans

On the 16th we left Little Rock for the 275 mile, two day run to Natchez, Mississippi. Our course was almost due south, and more changes were evident in the landscape. We were entering the deep south Bayou country, and there were cotton fields by the miles. Our evening stop was in a little town called Lake Village. The town derived its name from lake Chicot, a bypassed half doughnut shaped body of water that had once been part of the Mississippi River. Lake village has two claims to fame. First, it had been the original county seat until Mississippi River eroded its banks and washed it into the river, lock stock and courthouse. It was rebuilt and again was washed into the river. Secondly, Charles A. Lindbergh, four years before he flew the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic, was forced to land at Lake Village at night. He corrected the plane’s problem, and seeing the full moon shining brightly, took off before dawn. It was an historic incident as it was the first recorded night take-off in history. Later at the motel John Grundy offered a newsman and his wife a ride. The passengers also included Whitney Snyder and the Henrys. The reporter, Steve Russell, guided us to the old homes along the lake frontage which were the picture of Victorian elegance. We sped over some narrow dirt roads with right angle turns every so often and John really slid the old Packard around the curves. It wasn’t until after the hair-raising ride that we learned that the newsman’s wife was expecting a baby.

The 17th was warm and clear and the crop dusters were in full flight before the sun rose. We breakfasted at the local truck stop and headed south. We soon were greeted by the Louisiana welcome sign and passed through extensive cotton fields, rice paddies, and beautiful pecan orchards. One small town just off our route deserves special mention. Its high school was waterproof, the gas station was waterproof, and even its post office was waterproof. The little town, once on the Mississippi and now bypassed, was named Waterproof, Louisiana. We continued down the west side of the Mississippi along a branch of the Missouri-Pacific Railroad. It’s hard to believe, but we saw about 16 miles of parked empty freight cars. Gaps, of course, had been left for small roads and private lanes to cross the tracks, but the number of unused freight cars is an indication of the decrease in durable goods shipments.

Russ and mary Benore’s 1912 Abbott detroit

dorothy conant in their 1913 locomobile. husband jim is behind the camera

The Henry’s Packard had more trouble. The manifold broke again, but the M.Ds (Motorcar Doctors) re-patched, re-splinted and bound up the whole mess to hold for the rest of the trip; all done in the pouring rain. One umbrella kept the manifold dry. The whole Natchez aera was beautiful, and we would have liked to see more of it.

The first part of our drive on July 18th was through gently rolling country and past noteworthy ante-bellum homes. The entire area was green, lush, prosperous horse country with pretty barns and white fences, a sharp contrast to the open ranges in Utah and Nevada. We continued south on the east side of the Mississippi and re-entered Louisiana on U.S. Route 61. The area became more commercial as we approached Baton Rouge, being built up all the way to New Orleans. The heavy traffic and one way streets in the French Quarter made driving a severe challenge in an antique car, but we found the motel with little trouble. I was thankful for this because the Karl Summer Srs. followed us trustingly.

The 19th was our first real “rest” day in 700 miles, and there was plenty to do in changing oil, greasing, cleaning, and for those that had the time, polishing brass (in vain as it rained again!). There just weren’t enough hours to decently see the sights of New Orleans. In the evening there was a dinner at the Court of Two Sisters, a historic and renowned restaurant in the middle of the French Quarter. Each driver was presented a Certificate of Merit, signed by the mayor of New Orleans, Ernest M. Morial, with the official seal and a key to the city. This was arranged by Brod Bagert, a former councilman. Councilman-at-large Sydney Barthelemy represented the mayor and made the presentations.

Elegant brass on the grass at milford barkers, with james conant’s 1913 locomobile in the foreground

Dorothy conant had to stretch to chat with jean hecht

Dr. bud stanley, 1914 cole (left) pulls off to talk with james thomas, 1914 knox

The tour left New Orleans on July 20th and headed east on Route 90, the Gulf Coast Highway, taking us past the historic resorts of Bay of St. Louis, Pass Christian, and Ocean Springs. It seemed only a few years ago that the 1970 Glidden Tour took us along this same coast road just after the devastation of hurricane Camille. Roofless homes, garments and other objects hanging from trees, and the destruction of the whole waterfront told the story of loss and suffering in the area. On the positive side, it was good to see it all rebuilt and the area thriving. Our route left Louisiana and passed into Mississippi once again and then entered Alabama near Grand Bay. Our checkpoint was the Ramada Inn in Mobile. Mobile is a city that has been under the flags of Spain, France, Great Britain, the American Colonies, the Confederate States, and finally the U.S.A. The Illinoisans provided us with a delightful restoration hour. We appreciated the generosity of the Grundys, Lederers, Pearsons, Winslows and Youngs.

On July 21st the tour left Mobile and headed east for 330 miles to Valdosta, Georgia. The terrain of western Florida is gently rolling cattle, lumber, cotton, and tobacco land and a pleasure to tour in an old car. A group of us stayed in Marianna, the only night we spent in Florida.

Dr. peter kesling’s 1910 velie leads peter morgan’s 1913 Ford in the rain at jekyll island

“cork” simmelink’s 1914 cadillac which made the oregon-pebble beach-jeckyll island-oregon trip of more than 8,000 miles

The 22nd found us heading east through beautiful farmlands and many lovely homes. We were surprised to note that the rural mailboxes all faced backwards (away from the road), and we enjoyed passing a town named Two Egg. The mail boxes were turned around so that the RFD carrier could get off the rather narrow paved road, go over on the wide grass shoulder and make the delivery without risk of being hit by passing vehicles. Our luncheon was generously provided by Milford and Ruth Barker in Havana, Florida. The Barkers had been on the 1976 and 1979 tours, but in both cases were compelled to leave the trip because of emergency problems in the family. It was great to see the Barkers and their cars. Their big Oakland looked ready to go on another trip once again. That evening the “Rookies” gave us a party. It was a great spread of fruit, cheeses, and other hors d’oeuvres, and the upstairs veranda with the swimming pool below, completed the picture.

Friday, July 23rd, was suddenly upon us. The day that had looked like an impossible dream when we were assembled in Pebble Beach, 3,600 miles and eleven states behind us, had finally arrived. When we were crossing the causeway through the salt marshes to Jekyll Island and could actually see the Atlantic Ocean, we realized with regret that this was indeed, the end of the tour. For thirty days we had been exposed to cold, snow flurries, rainstorms, heat, high winds, and 600W grease to such an extend that we had to remind ourselves from time to time that we were really on a pleasure trip. It was quite difficult, too, to explain to passersby that we really were on a motoring trip across the country for a vacation.

At 5 P.M. Millard presented the completion plaques. It was fitting to have a dreadful downpour during the ceremony. We started in the rain (they called it fog in California) and we ended in the rain.

It was the late opera star and old car enthusiast, James Melton, who said thirty-five years ago, “Now that we have all these cars fixed up, let’s take them on a tour and see how they do.” Touring has been a way of life for many antique car owners since Melton got us started, but no one dreamed of three and four thousand mile tours until Millard Newman proposed a Transcontinental Tour to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the first leg of the Around the World Race in 1908. After the completion of the 1968 tour there had been no thought of a second one, but after some urging Millard agreed to run a cross country trek form Montreal, Canada to Tijuana, Mexico. It should have been the trip to end all trips, but the enthusiasts wanted another and another and another! During our final banquet on Jekyll Island there was some conversation about getting ready for 1985. You might think that 17,446 miles covered in the five Transcontinentals should be enough, but it looks as if long distance touring is here to stay.

tour director millard newman presided at the awards ceremony at the jekyll island hilton

1911 thomas flyer of bill and cathy winslow

Our tour was a success in every way. Our safety record was perfect in spite of several harrowing episodes. Millard presided over the final awards banquet. Dick Flemings was on hand to award the president’s Cup to John Hovey and his beautiful 1907 Pierce Great Arrow. It was the oldest car and had a perfect score. Millard made the other awards in short order. Whitney Snyder with a needlepoint belt, picturing red Rolls-Royces. It was fitted with an engraved silver buckle. A gift of a series of boxes of fruit will be arriving monthly from the Harry & David orchards so the Newmans won’t forget us and our appreciation during the coming months.

All the awards were fitting and appreciated, but the main reward for the trip was the safe completion of the tour and the inner satisfaction of knowing you and your car were properly prepared for the challenges we faced. It speaks for itself that 33 of the 51 entrants had perfect scores and that 47 cards made it all the way to Georgia.

These old articles are just fantastic and we’d love to know more about the 1982 Pacific to Atlantic Transcontinental Reliability Tour. If you have any stories, photographs or know the model numbers of the vehicles pictured, be sure to leave a comment below.